Major Chords in Music: How to Use the Cheeriest Chord

If there’s anything that you should learn when getting started with learning an instrument or learning music theory it’s a major chord progression.

Major chords in music are ubiquitous—it’s hard to find a song that doesn’t use a major chord or some variation on one. The C major chord is especially popular.

So in this article, we’ll explore what there’s to know about major chords, how they work within the major and minor keys and how you can apply them in your songwriting.

Plus we’ll open the lid on some more advanced topics like major chord extensions.

But first, let’s dive into the basics.

Theory guides, production tips, new free plugins, gear guides and more—delivered weekly

Keep up with the LANDR Blog.

What is a major chord?

A major chord occurs when three notes are played together to form what’s known as a triad. The notes that form a major chord triad are the root, a major third and a perfect fifth.

For example, a C major chord will consist of C—the root note, E—which is a major third from C—and G—which is a perfect fifth from C.

The A major chord is A, C# and E.

The E major chord is E, G# and B.

The major triad is the most basic form of a major chord, but other major chords can be built with additional notes as long as they include the characteristic major third interval relationship with the root.

Why do major chords sound happy?

There are a few theories about why major chords in music sound happy—and why minor chords, on the other hand, sound sad.

Most likely these perceptions are cultural—those who grew up listening to Western music tend to make this association, while listeners accustomed to African or Asian music may not.

Even in western music, most pop music listeners consider pop music to be “happy”, while most chart topping tunes are written in minor keys.

So it’s very subjective as to whether a major chord progression actually sounds “happy”.

Major chord progressions may sound happy to Western listeners because they have pleasing intervals that interact with each other in certain ways. They also belong to the Ionian music mode, which is associated with a happy and positive sound.

How many major chords are there?

There are 12 major chords: C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, Ab, A, Bb and B.

That’s because there are 12 notes in Western music: A, B, C, D, E, F and G, plus five half-steps in between those notes.

A major chord starts with one of those notes and then plays the third and fifth notes after that.

Of course, each chord has three inversions which we’ll discuss later on in this article.

What is a major third interval?

A major third is exactly four semitones (or half steps) up from the root note.

If you look at our C major example, E is up four half steps up from C which is why it’s the major third in a C major chord.

What is a perfect fifth interval?

A perfect fifth is exactly 7 semitones up from the root note.

In our C major chord example, G is 7 half steps up from C.

If you want to learn more about intervals we’ve covered every interval in music in previous posts—you’ll even find examples from popular music for each one!

Major chord inversions

Of course, there are different ways to play major chords progressions—because the notes that comprise any major chord can be rearranged.

In music theory, there are three main inversions in which a major chord can be played so let’s look at those chord voicings.

Root position

When a major chord is not inverted it is played in what’s called root position.

The reason it gets that name is because the root note is played at the bottom of the triad with the major third and perfect fifth stacked on top.

So, in a C major triad you’ll find C at the bottom, E in the middle and G on top.

First inversion

In first inversion, the root note moves to the top of the chord so that its lowest voice becomes the major third, with the perfect fifth in between.

Taking our C major example, a first inversion C major chord uses the notes E, G and C in that ascending order.

Second inversion

In second inversion the root note is found in the middle of the chord and the perfect fifth note is now the lowest in the chord with the third on top.

Again, using our C major example, its second inversion form would use the notes G, C and E in that order.

Using major chords in chord progressions

It may be tempting to gravitate towards major chords in your songwriting because they are considered to be “happy”.

The reality is that just like all other chords, major chords have their special place within a chord progression.

They won’t necessarily sound right if you don’t use them in the right way.

The best way to identify where a major chord belongs in a chord progression is by looking at the scale degrees of whatever key signature you’re working in.

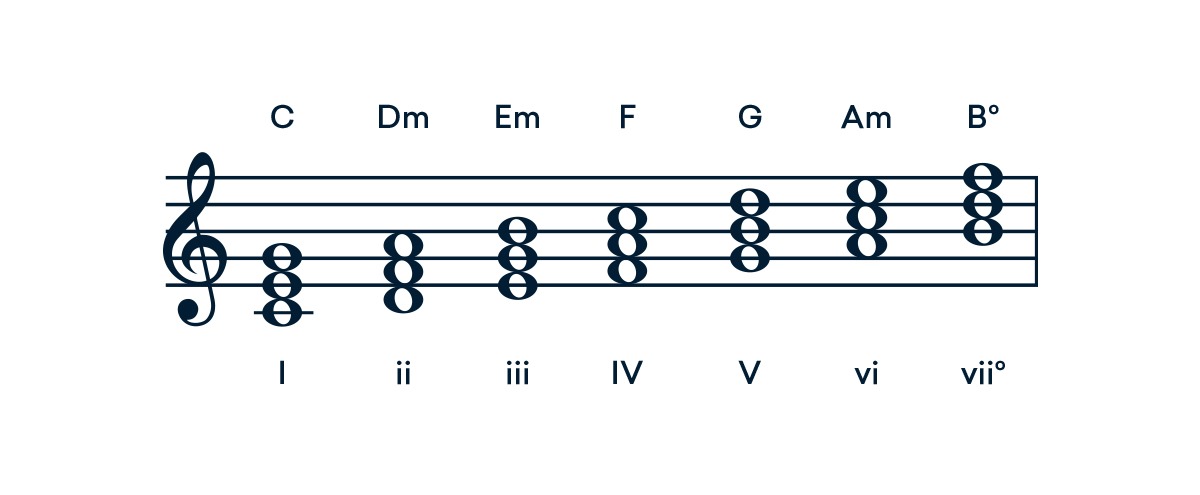

In a major scale (or major key), major triads form when built on the first, fourth and fifth scale degrees.

For example, in a C major you can build a triad on each degree of the scale.

If you try it, you’ll see that the chords built on the fourth and fifth-degree are both major. While the chords on the second, third and sixth-degree are all minor chords. These are called diatonic chords because they’re built using only the notes available in the key of C major.

That’s why the 1-4-5 chords are used in many common chord progressions—they’re all built on the major scale degrees that comprise major chords.

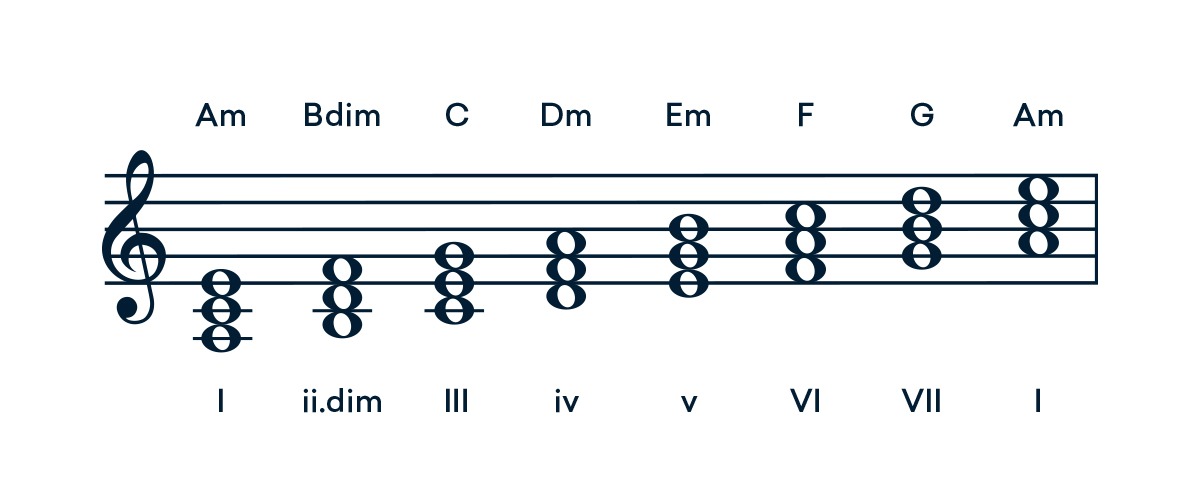

You can build a major chord within the minor scale too—the major chord just exists on certain degrees of the minor scale.

Take a look at this example that uses natural minor scale in the key of A minor.

Building a triad on each degree of A natural minor produces major chords on C, F and G, the third, fifth and sixth degree of that scale.

If you don’t understand why those major triads form there, it makes more sense when you think about the circle of fifths.

Take a moment to get familiar with the circle of fifths if you haven’t already—it’s probably the most important concept to understand when learning western music theory!

In the circle of fifths, A minor is the relative minor key to C major and F and G are the adjacent keys to C major—they’re also the major chords found in the example from C major above.

Major chord extensions

Major chords in music don’t stop at triads, in genres like Jazz you might hear about major chords like the Major seven or Major nine.

These chords essentially add a seventh or ninth interval on top of a major triad, it’s one-way jazz music adds an extra level of color and dissonance to the chords it uses.

But essentially the same principle applies—except you add the seventh or ninth to the inversion position of your chord.

Here’s how a Major seventh chord in root position sounds for example.

There are many more ways to think about chord extensions within music theory, fortunately, we’ve written about chord extensions in greater detail.

A major stepping stone

The major chord is usually the first place students start when learning music theory—especially the C major chord.

In many ways it makes sense, the major chord isn’t overly complicated to wrap your mind around and start using in music.

But, don’t get hung up on major chords for too long—you’ll probably get bored!

Trust me, there’s a lot out there in the world of music theory that’s much more interesting to get into if you really want to get deep into it.

For now, practice your major triads, scales, chord progressions and cadences and once you’ve mastered those you’ll be ready to get into the fun (slightly more advanced) stuff.

Ready to master major chords and create powerful music that captures any emotion?Join the LANDR community for access to tutorials from expert musicians on chords in music and tons of other topics.

Gear guides, tips, tutorials, inspiration and more—delivered weekly.

Keep up with the LANDR Blog.