Major Scales: Learn Scale Degrees, Key Signatures and More

Major scales are an essential building block of all western music. It's one of the most commonly used musical scales.

While sitting down and practicing the major scale isn’t anyone’s idea of fun, the payoff in the future is rewarding.

By knowing your major scales inside and out, you’ll be able to navigate through all aspects of music theory.

In this article I’ll explain what major scales are, and how you can begin to understand them and use them in your music.

What is the major scale?

The major scale is a seven note scale that consists of a series of whole steps and half steps. The half steps exist between the third and fourth, and seventh and eighth scale degrees.

Another name for the major scale is the diatonic scale. This simply means that the half steps in the scale are spread out as much as possible.

Here’s a video and sound example of the C major scale played on a standard keyboard.

If this sounds confusing, don’t worry! We’re going to break down all the whole steps, half steps and scale degrees in this article.

Let’s get started.

How to build major scales

Looking at the piano is the easiest way to begin understanding the major scale.

The major scale is a seven note scale that consists of a series of whole steps and half steps

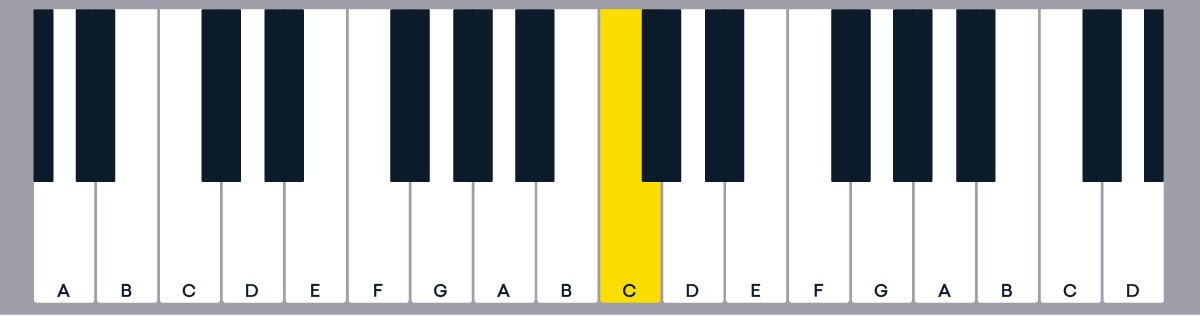

If you look at all the white keys on the piano, you’re looking at the C major scale.

The C major scale starts on the white key that comes before the two black keys. This is the first scale degree.

Before we start building the major scale, it’s important for you to know about whole steps and half steps.

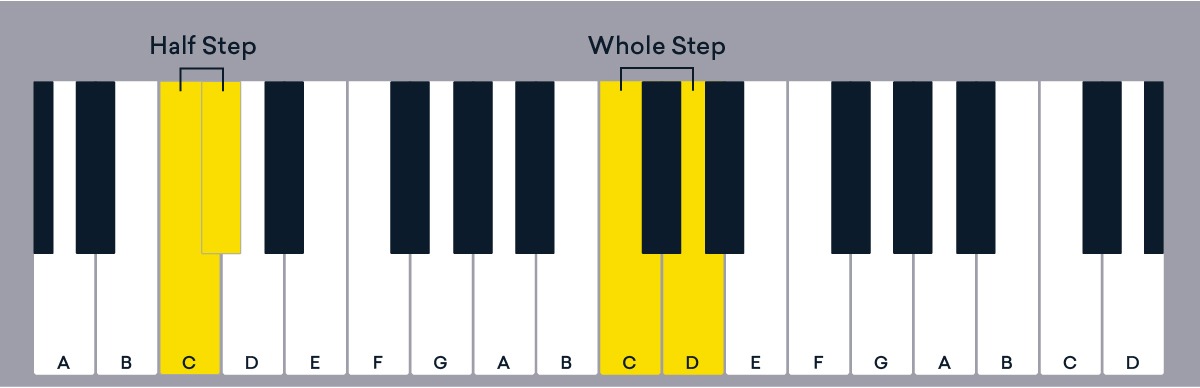

One half step is the distance from one note directly to the next one. One whole step is equal to two half steps.

One half step is the distance from one note directly to the next one. One whole step is equal to two half steps.

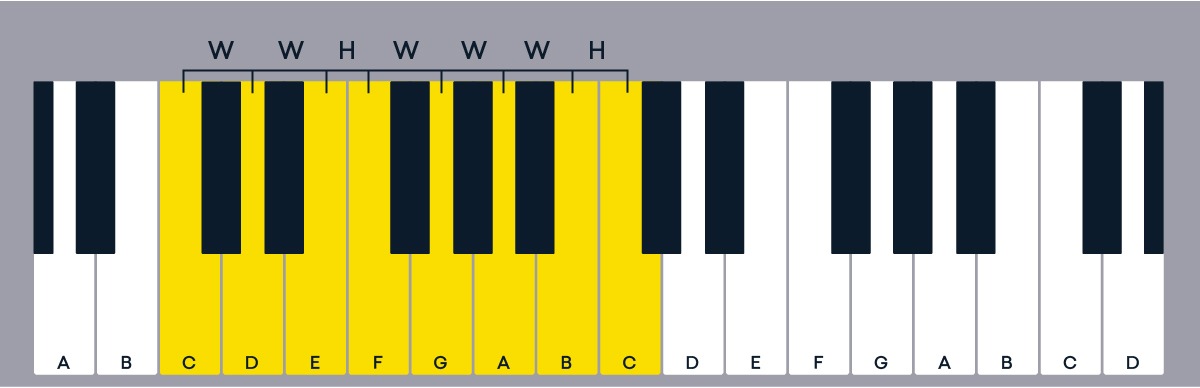

Now look at the piano. Find a C, and use the following formula to play a C major scale: whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step.

As you play the scale according to the whole steps and half steps, you’ll also be playing each scale degree from one to seven.

Congratulations! You just played a C major scale. This scale tells you the musical key of C major: no sharps or flats.

Building major scales in other keys

You’ll be able to build a scale starting on any note if you can do it in the key of C major.

You’ll be able to build a scale starting on any note if you can do it in the key of C major.

When you build major scales in other keys, you’ll start to use the black keys on the piano to fit the major scale formula.

Let’s take a look at the major scale in D major.

Start on D, and use the major scale formula

D whole step to E, whole step to F#, half step to G, whole step to A, whole step to B, whole step to C#, half step to D.

You’ll also notice that the key signature of D major also contains F# and C#—that’s because a major key’s sharps or flats are defined by that key’s major scale.

This might take a bit to get used to once you start practicing it. You’ll begin to get more comfortable with it as time passes.

After a while you’ll feel it start to become more natural. Applying this information to other areas of music will come quicker and easier to you.

Key Signatures in Music Theory

Key signatures are an essential aspect of music theory, defining the tonal center and scale of a piece of music.

Each key signature consists of a specific combination of sharps or flats that applies to certain notes throughout the piece.

The key signature indicates which major (or its relative minor) key the music is in. For example, a key signature with one sharp is G major (or E minor).

By placing sharps or flats at the beginning of the staff, the need for frequent accidentals in the music is reduced, making the sheet music cleaner and easier to read.

Understanding Key Signatures

Each major key has a unique key signature. C major has no sharps or flats, G major has one sharp (F#), D major has two sharps (F# and C#), and so on.

Don’t be afraid to take this formula through the circle of fifths and practice every musical key. The circle of fifths helps in understanding and memorizing key signatures, showing the relationship between different keys and their respective signatures.

For music producers, a solid grasp of key signatures is invaluable for arranging, composing, and transposing music, ensuring that all elements of a track are harmonically aligned.

Modes of the major scale

The major scale is also used to build the musical modes. The modes contain the relative minor scale, as well as other frequently used scales.

The modes are all based on the major scale formula.

The modes are all based on the major scale formula.

We call the major scale the Ionian mode, because it starts on the first scale degree. The other six scale degrees in the major scale will give you different modes.

For example, starting the C major scale on the second note D, will give you D Dorian mode: D E F G A B C D.

Continue this pattern by starting the C major scale on any note. This will give you different modes of the major scale, and you’ll start to hear the different tonal qualities as you play them.

Check out our in depth guide if you want to dive deeper into modes in music.

Major scales in music

The major scale is considered the basic scale in western music. It’s the bright, stable sound we associate with happy-sounding music.

The major scale is the backbone of functional harmony in music. Remember the tone-semitone pattern I talked about before?

The position of the semitone intervals is what produces the sense of tension and release in progressions of chords built with the notes in the major scale.

That might sound a bit theoretical, but it’s the reason why the major scale can be found absolutely everywhere in music.

With such a fundamental scale, it’s pretty hard to say how best to use it. The best advice is to follow your ears and let your own creativity be your guide.

Exploring the Major Blues and Pentatonic Scales

The major pentatonic scale, a derivative of the major scale omitting the fourth and seventh degrees, offers a simpler and more melodic sound.

It’s a staple in various musical styles, prized for its consonant and versatile nature. For example, the F# major pentatonic scale comprises F#, G#, A#, C#, and D#.

Here’s a video example of the F# major pentatonic scale on a traditional keyboard.

The major blues scale takes the major pentatonic as its base and introduces a chromatic ‘blue note’, adding a distinct bluesy coloration.

This scale, especially prominent in blues and jazz, is known for its expressive quality. In E major, this scale would be C, D, Eb, E, G, A, C where Eb acts as the soulful blue note.

Here’s a video example of the C major blues scale on a traditional keyboard.

These scales are not only central in improvisation and soloing across different genres but also play a significant role in shaping the emotional tone of a piece.

Experimenting with these scales over chord progressions can significantly enhance your musical expressiveness and add new dimensions to your compositions and productions.

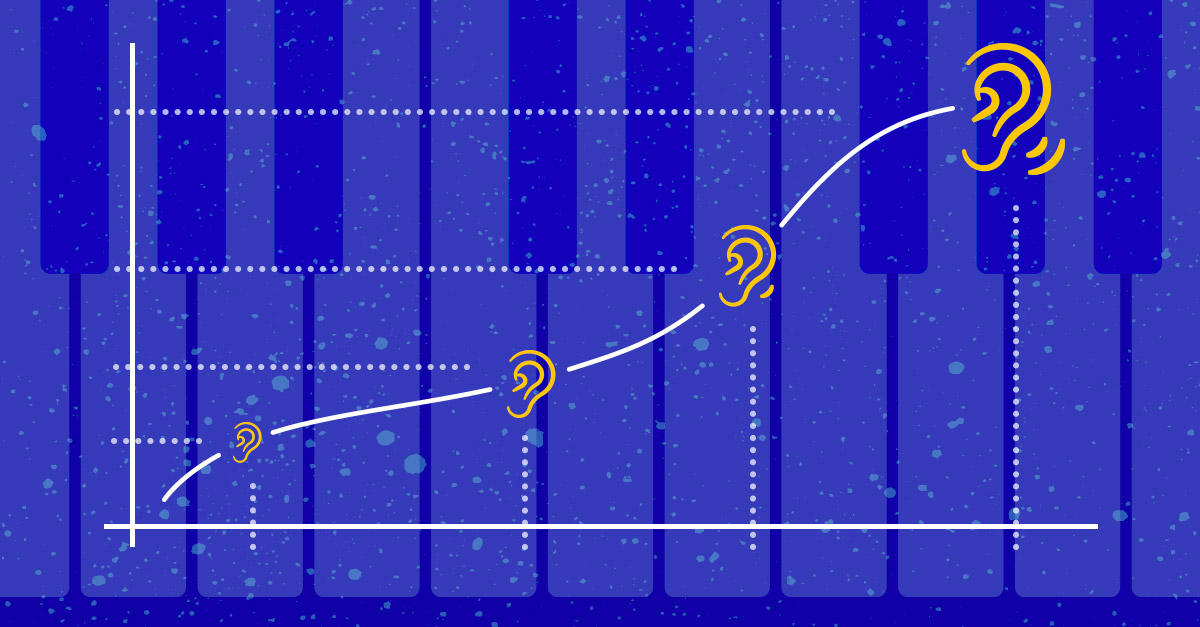

Hearing the major scale

The major scale is the most important rudiment of musical ear training.

Learning its scale degrees by ear will allow you to classify musical intervals, identify the root of a chord in a progression and transcribe melodies.

To develop this skill you’ll need a solid grasp of the major scale’s construction. But ear training practice is also essential.

Check out our guide to ear training to learn more:

Major scale practice tips

If you’re looking to become fluent in the major scale, you’ll have to incorporate it into your practice routine.

It may seem like all you need to do is play up and down the sequence of notes, but there’s a lot more you can do to play major scales musically.

Here are four practice tips you can use to increase your command of the major scale:

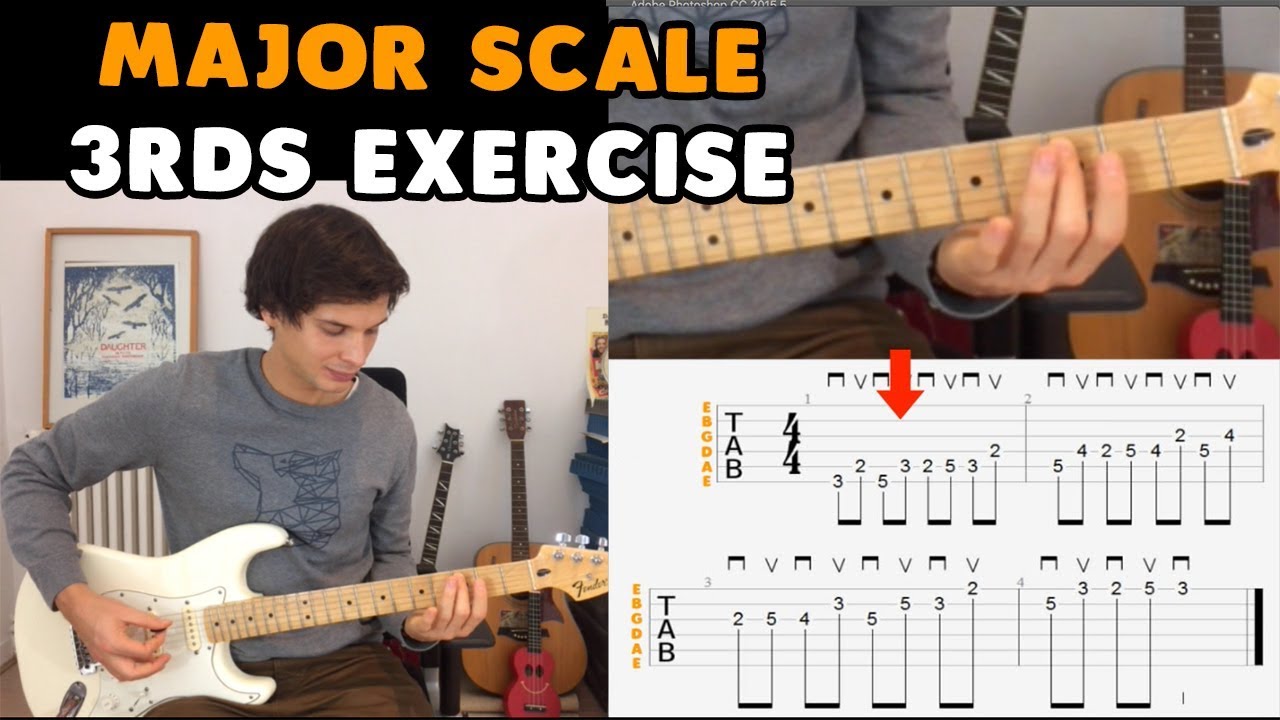

1. Alternate thirds

Try playing up the major scale by skipping a third and then descending a second before skipping up again.

Ascend up two octaves and play the pattern in reverse order as you descend.

The result is a pleasing cascade of alternating intervals that’s easy to work into a melody.

Alternating thirds on electric guitar.

2. Diatonic arpeggios

Stack thirds one top of each other to play a triad arpeggio as you move up and down the notes of the major scale.

If you play from bottom to top, you’ll build each of the key’s diatonic chords in succession.

This exercise is helpful for memorizing the order and qualities of the diatonic chords as well as playing them melodically.

3. Fill in skips

Choose an interval like a 4th or 5th to skip in an ascending or descending direction.

Fill in the intervening notes in stepwise motion from the note you started on.

The result is a pattern similar to Bach’s classic “Minuet” melody that can give you ideas for improvisation.

4. Play the 12 keys in order

Finally, one of the most important major scale skills is feeling at home in all twelve keys.

To play this exercise simply ascend and descend the major scale in order and proceed to the next key without breaking your rhythm.

If you follow the order of the circle of fifths, you’ll only need to add one accidental each time you progress to a new key.

This helps you drill your key signatures, learn your scales and remember the circle of fifths all at the same time!

It’s major for a reason

Don’t forget the major scale in your practice routine. Practice it in all 12 keys. Use it to create new melodies and harmony.

Once you have this scale in your ears, you’ll be a natural when you go to create your next song.

Gear guides, tips, tutorials, inspiration and more—delivered weekly.

Keep up with the LANDR Blog.