Is Sampling Legal? 10 Facts for Sampling Audio Safely

How do you sample music without running into problems with music platforms and the law?

Sampling is the foundation of so many styles of music, yet it also has a long history of legal trouble and controversy.

The last thing any musician wants (especially an independent musician) is to end up getting their music taken down or to face costly legal consequences.

So, is it still possible to safely create music using found sounds, or is sampling a dying art? These 10 facts should set the record straight.

Let’s get straight to it.

Contents

- Know your terms and know your samples

- Transforming samples doesn't keep you safe

- Owning a beat doesn't mean owning sample rights

- Public domain isn't always simple

- Clearance can be hard

- Proof of rights matters

- Two permissions are required for clearance

- You can avoid clearance creatively

- Field recordings can still be risky

- Royalty-free is safest, with some exceptions

Note: This article is for informational purposes only and is not to be taken as legal advice.

Know your terms and know your samples

OK, first things first. The word “sampling” can mean a lot of different things, so the most important thing to learn is the difference between various kinds of samples.

Generally speaking, “sampling” refers to taking sounds from preexisting sources like music and movies. But it can just refer generally to the act of using any piece of sound (including ones that you make yourself) in a music production context, especially through the use of a sampler or sampling plugin.

For the purposes of this article, we will use the word “sampling” to refer to the use of sounds that you did not create yourself and that you do not have the legal rights to use.

In some places, we’ll refer to royalty-free and public domain samples, and we’ll make that clear where it shows up.

Just be aware that when you’re using sounds in your music that you did not create from scratch, you should know where the sounds came from.

It’s not uncommon to come across .zip folders of sample collections given away for free on forums and blog sites that actually contain samples which were not cleared when they were originally taken from the source.

This means it’s possible to be liable for an unauthorized sample without even being aware of it. So, it bears repeating: know your sources!

Transforming samples doesn’t keep you safe

This is one of the most important things for any producer to remember about sampling, as it’s a source of many misconceptions.

Contrary to what you might think, heavily processing a sample from a copyrighted piece of music doesn’t necessarily make you immune to legal liability.

In 2005, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled on the Bridgeport Music case, which involved a two-second, heavily altered sample taken from a Funkadelic song without permission.

The court decided that, despite the changes made to the sample and its short length, any amount of copying from a protected sound recording required a license.

While this case shaped American industry practice, especially in the regions covered by the Sixth Circuit, sampling laws can vary between countries. Because of territorial differences, it’s important to understand the laws that apply where you live and where you plan to release your music.

The main point is that transforming or manipulating a copyrighted recording does not guarantee legal safety. The safest approach is to treat any recognizable or traceable sound recording as protected unless you have permission or a license to use it.

Owning a beat doesn’t mean owning sample rights

If you buy a beat from a producer, does that give you the ownership to create new music (derivative works) from that beat? Unless you’ve reached an agreement that does allow for this (which is rare) the answer is no.

Buying a beat from a producer does not automatically give you the right to use every sound that appears in it. For one thing, sampling from it without permission would infringe on the producer’s copyright.

But in addition to this, many producers of course work with third-party sample packs or pull sounds from sources they are not legally allowed to redistribute. This means that sampling a beat could pass that liability onto you.

In other words, if the beat contains an uncleared sample, you can still be held responsible for using it.

Always ask the producer where their sounds come from, make sure all agreements between the two of you are clear, and make sure they can prove that every element of the beat is legally clean.

Public domain isn’t always simple

Public domain material might seem like the safest option when it comes to digging for samples, but it can get confusing.

For instance, a composition may be in the public domain, yet the recording of that composition might still be protected by copyright.

If you sample a modern orchestral performance of a public domain symphony, you are still sampling a copyrighted recording.

The only truly safe public domain recordings are those where both the underlying composition and the sound recording itself are no longer under copyright.

When in doubt, always verify the status of both. You don’t want to end up liable for a sample that you thought was totally fair game.

Clearance can be hard

Like a lot of things involving copyright and intellectual property, sample clearance can be a long and unpredictable process.

It often involves identifying the rights holders, sending requests, waiting for responses, and negotiating terms. In fact, many owners simply do not respond at all.

Some, on the other hand, will respond but decline your request. Others ask for fees or percentages that may be way out of budget for an independent artist.

Because of this, even major-label releases sometimes change samples late in the production process, typically replacing them with similar sounds that were made from scratch (we’ll revisit that later on).

If you plan to clear a sample, be prepared for delays and understand that you may need alternate versions of your track in case permission is denied.

You definitely don’t want to put all your eggs in one basket by making your tracks in ways that depend on samples you haven’t even cleared yet. Never assume that you can get clearance when you don’t know for sure!

Proof of rights matters

Realistically, producers can get permission to use samples in many different ways, including verbal or informal agreements. This can potentially lead to issues if the agreement isn’t backed with legally-binding documentation.

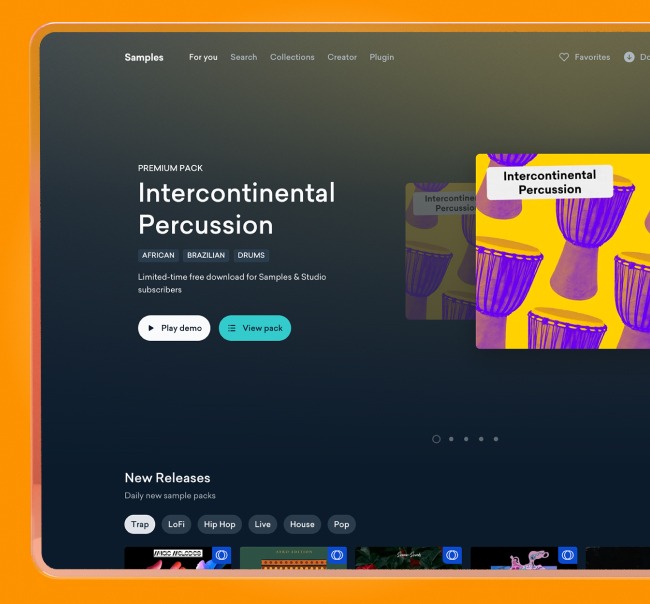

Music distribution platforms like LANDR have processes in place to detect the unlicensed use of copyright-protected material, and if your music shows signs of infringement, you will most likely be asked for proof of rights.

This can include license agreements, receipts, contracts, or written permission from collaborators.

If you don’t provide proof, your release can be delayed or rejected.

So, even if you sampled a drum session recording made by a friend who told you it was okay to use it, it’s always best to err on the side of caution. Ask your friend to sign a document that gives you permission so that you can avoid distribution issues down the road.

Another important detail: don’t assume that you can upload a release without your proof of rights and provide it later when asked. If you acquired clearance for sampled material, provide your documentation from the outset!

Two permissions are required for clearance

Music copyright operates in two separate but parallel domains: music compositions and music recordings. We outline this in our article on music publishing.

This means that when you clear a commercial sample, you usually need two separate kinds of permission.

One is for the composition (the lyrics, melody, etc.), which is owned by the songwriter or publisher. The other is for the sound recording (the actual recording of the music that you are sampling), which is owned by the performer or record label.

These two rights are completely different and are often held by different people or companies. It’s not uncommon for people to think that they’re in the clear just by licensing a sample from the recording, only to find out later they didn’t acquire the necessary rights from the publisher or songwriter.

This also means that if you want to work around sampling law by simply using and re-recording the same melody or lyrics from a copyrighted song, you’re violating the rights of the songwriter and could be liable.

No matter what, you need written approval for both the composition and the recording if you want to legally release music that re-uses a recognizable sample or musical element.

You can avoid clearance creatively

It might seem like all of this sampling law stifles creativity, but that isn’t necessarily the case.

If you hear a sound in a song that you want to sample, but you don’t have the resources to clear it legally, you can still use it for inspiration. That is, as long as what you create is sufficiently different from the original.

There are, in fact, some aspects of music that cannot be copyrighted and that you’re safe to mimic and reinterpret if you want.

Synthesizer patches, for instance, cannot be copyrighted. This means you can find or create a synth patch that sounds like the one in the song you’re inspired by and write a new, original melody that is similar in mood.

Drum patterns also cannot be copyrighted. You could record a drum track with a similar pattern and even a similar effects chain, but as long as you record and process it from the ground up, the risk is far lower.

Believe it or not, chord progressions also cannot be copyrighted. As long as you are not copying a melody, and as long as you’re not re-using distinctive voice leading from another song, you can use chords and harmonies as jumping-off points to create your own compositions.

However, there are always important nuances to bear in mind here, as songwriting copyright is significantly more complicated than recording copyright.

For instance, certain elements when combined together, even rhythm and harmony, can potentially trigger lawsuits if they too closely resemble an existing composition. While this is very rare, it’s not impossible.

The most famous example is the case Gaye Family v. Thicke & Pharrell, which concerned the song “Blurred Lines”. The court ruled that the overall style and character of Blurred Lines plagiarized that of Marvin Gaye’s song “Got to Give It Up”, even though melody and lyrics were not replicated.

Field recordings can still be risky

A field recording is any recording that you make outside of a studio context. This could be a public place, out in nature, or an interior space that is not used for music production or recording.

Field recordings feel like they should always be safe, but that is not necessarily true.

If you record copyrighted music playing in a store, a television in the background, or any identifiable performance of a protected work, you may still be sampling copyrighted material.

Some locations have restrictions on recording as well. Disneyland is an example of a venue that forbids the commercial use of any video or audio recordings taken on the premises.

It can also be tempting to record buskers who perform on the street or in public transit spaces. However, if you use these commercially without the performer’s permission, it’s not impossible for them to pursue action to be paid royalties and/or damages. In fact, this is true even if you record a conversation you have.

In short, always be mindful of what is happening in the environment when you record, and always secure the necessary permissions for commercial use.

Royalty-free is safest, with some exceptions

The bottom line is this: better safe than sorry. If you want to make music using samples while staying 100% sure that you’re legally safe, royalty-free samples are the way to go.

On top of this, however, some platforms have restrictions even on the use of royalty-free samples.

For instance, if you want to monetize your music through YouTube Content ID, TikTok, Instagram, or Facebook, these platforms will require that all of the sounds in your music are entirely original and/or that you have the exclusive rights to any elements you acquired externally.

Just because a sample is royalty-free does not mean you have exclusive rights to use it. In fact, royalty-free samples are almost always used by multiple people.

So, to summarize this point:

1. Royalty-free samples allow you to create sample-based music and release it commercially via streaming, download, and radio.

2. When it comes to monetization on user-generated content platforms, fully original or exclusively owned samples are usually required.

3. Because of this, these forms of monetization are more highly curated by distributors in order to stay in line with platform policies.

Ultimately, if you want to maximize the revenue you get for your music and minimize your liability, make your music as original as possible, always know how you source your sounds, and always get the permissions you need so that you can avoid headaches later on!

Gear guides, tips, tutorials, inspiration and more—delivered weekly.

Keep up with the LANDR Blog.