Detroit Legend DJ T-1000 Talks Cutting Tape and Airtight Studio Setups

You can recognize a true techno head if their eyes light up when someone says ‘DJ T-1000.’

Alan Oldham’s (aka DJ T-1000) career stretches back to the days when ‘techno’ wasn’t even a word yet.

Both a visual artist and a DJ/producer, his journey started in the birthplace of techno: Detroit.

Oldham was among the trailblazers who invented the genre all together—producing and coming up alongside the Belleville Three and Jeff Mills. He started DJing during in the early 1990s in the Underground Resistance collective. Oldham is now based in Berlin and his studio is as minimal as it gets: a Maschine and a laptop.

Oldham spent his early years in music as a host on Detroit’s public radio station WDET-FM. His show ‘Fast Forward’ was one of the earliest electronic music programs in the city. In 1987, Oldham illustrated the cover of his friend Derrick May’s first record. Oldham went on to illustrate hundreds of immaculate record sleeves including many for the label DJax-Up-Beats.

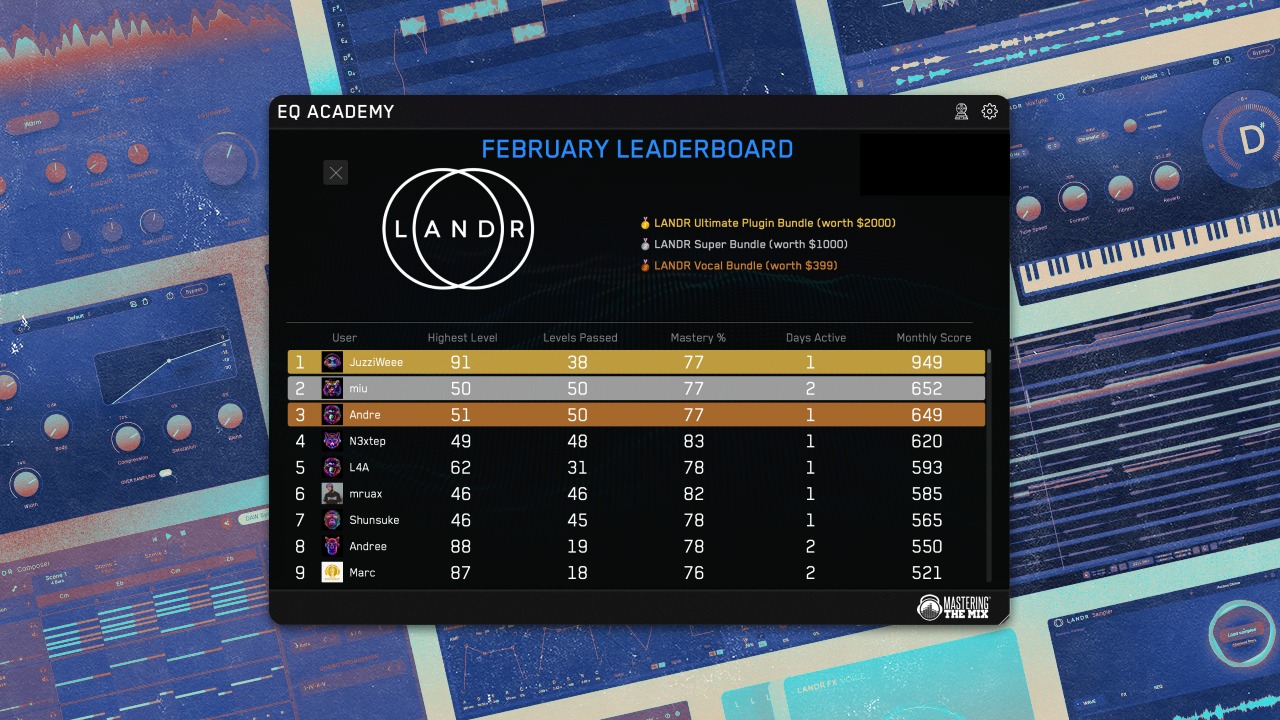

DJ T-1000 is also an important part of the LANDR Community. When I asked him how LANDR was working for him he simply said “Everything is great, I’m mastering my ass off right now.”

Even with legendary veteran status (he was editing his first tape recordings with a razor blade) his perspective on current electronic music is a breath of fresh air.

We sat down to talk about starting a label, gear fetishism, his creative process and the state of techno.

What was Detroit like when you were first getting into music production?

Back in the early 90s, music production was a whole new world. I had hooked up with some guys who had a MIDI studio. They allowed me to hang out and absorb the gear. When I started making money DJing, I just went out and bought the same stuff they had. These were the days of the little ad newspaper, Tradin’ Times. No Craigslist, no eBay, no Amazon. We were still MIDI daisy chaining and recording straight to metal cassette. Then I’d take the tapes to the radio station where I worked, and bounced the cassette up to reel-to-reel and EQed it on the board. Then I’d edit it with a razor blade and tape. I’d do this after my show at 3-4 am when the WDET bosses weren’t there.

“We were still MIDI daisy chaining and recording straight to metal cassette. Then I’d take the tapes to the radio station where I worked, and bounced the cassette up to reel-to-reel and EQed it on the board.”

You’ve been involved with Detroit’s WDET-FM radio station. How important was radio in your development as an artist?

Very important as I had access to the station library and all the great music there. There was a lot to emulate, in my primitive way back then. Plus, I had late-night access to the production facilities there as well.

You are among the group of friends who are known for basically inventing techno. How would you describe the evolution of the genre over time, and where do you see its future?

I dunno. It seems techno has become a nerd/fanboy thing these days. Like an offshoot of computer geekery and the like. On the plus side, I see a lot of new and veteran female artists who are keeping it from becoming too frat-boyish. Some of the most successful artists right now are fusing techno with industrial and even adding vocals. This is keeping it fresh in my opinion, without selling the music out. Many vets are also still leading the way. Luke Slater, Steve Rachmad, Robert Hood, Dubfire, etc.

It seems techno has become a nerd/fanboy thing these days. Like an offshoot of computer geekery and the like. On the plus side, I see a lot of new and veteran female artists who are keeping it from becoming too frat-boyish.

How important is community to your music and what is the current techno scene in Detroit like?

I haven’t lived in Detroit in a long time, but I was very encouraged by my recent visit home. A lot of local cats are definitely keeping the home fires burning.

What city (or cities) do you spend the most time in? What’s the most interesting music scene in your opinion from the cities you know and why?

I’ve been living here in Berlin for the past 2.5 years and it’s the most interesting city in the world for art and music. It is the techno capital of the world, bar none. I don’t see any other city taking up the mantle in the future, either. There is an air of possibility and an energy here that I haven’t seen since New York City in the late 80s through to the 90s. If you’d told me back in the day that it would actually be cheaper to live outside America, I’d have thought you were crazy.

There is an air of possibility and an energy [in Berlin] that I haven’t seen since New York City in the late 80s through to the 90s. If you’d told me back in the day that it would actually be cheaper to live outside America, I’d have thought you were crazy.

You’re also a graphic designer who’s illustrated many record sleeves, most notably for Derrick May’s label Transmat. What is the relationship between a record and its cover? How important is album art today in your opinion?

Many times, the client will send me sound files on the record that I’m doing art for. Other times I vibe off the title, or they tell me exactly what they want, which is easiest for me. Judging from the art requests I’m getting, I’d say cover art is making a comeback. Labels are spending money on full sleeves again. As you know, the digital wave obliterated cover art. Now it’s taking prominence again in record shops.

What is your current production process like and how has it changed over time?

Nowadays, I’m on Maschine. Not on Ableton yet full-on, just dabbling there. Before I moved to Berlin, I had a full outboard MIDI studio largely unchanged since the olden days. But my competition had gone digital, started mastering louder and you could hear the difference. I bought Maschine from a guy here in Berlin when I first arrived and it’s a whole new planet. No more chasing down shorts in cables, no more MIDI chains, no more hiss. It’s airtight. What’s funny is now that I’m all in the box, my competition has dusted off the old outboard gear. Modular racks are the new gear porn on my Facebook timeline.

“No more chasing down shorts in cables, no more MIDI chains, no more hiss. It’s airtight.”

In 2006, you started a CD-only label called xfive. I’m very intrigued by the CD-only aspect of it. What is your relationship to music formats: vinyl, CDs, digital?

Back in the mid-2000s, I was stuck. My original, bangin’ techno style had died and minimal (Minus, Perlon, Kompakt, etc) had taken over. Many of the distributorss I’d worked with since Generator and Pure Sonik had gone out of business. There was no more money to press records. I wanted to change it up. CDs by this time had gotten cheaper and easier to put out, and I’d been doing a bunch of non-dancefloor tracks. My fiancée suggested I do a compilation of all those slower tracks. Thus, xfive. was born. I only did two official CD releases on that label, but people remember it, including you!

“As for vinyl, I do not fetishize it like a lot of people do. I have my old collection and my working crate, but I don’t rub records all over my body.”

As for vinyl, I do not fetishize it like a lot of people do. I have my old collection and my working crate, but I don’t rub records all over my body. When Traktor came along, I loved it and I’m still a big fan of it. Whether I play digital or vinyl depends on the gig.

CDs are still important also because fans still want the artifacts.

Techno as a genre has always been very open to machines and “non-human” elements to music creation. As music technology evolves how has your own process evolved with it?

I’m slow to adapt, but when I do, I’m all with it. I like the portable aspect of modern production. I.e. you can take your laptop anywhere and make music. As far as “human” elements, I’m looking to add vocals to my tracks soon. Plenty of cool people to work with here in Berlin…

If you’re in Europe, catch DJ-T 1000’s upcoming sets.

Gear guides, tips, tutorials, inspiration and more—delivered weekly.

Keep up with the LANDR Blog.